A tiger and a cow meet in a jungle. The scenario is tragically predictable: tiger kills cow, cow’s owner kills tiger. Yet in India, where repeated conflict can amount to sizeable livelihood losses and tiger declines, predicting where the scenario plays out is far from easy. However, a simple statistical method applied to mapping human-carnivore conflict could up the odds by helping people anticipate high-risk hotspots.

Our study, published in Ecology and Evolution, explored a technique that could be used to aid local people and park managers in managing livestock husbandry and carnivore deterrents. Based in Kanha Tiger Reserve, we accompanied villagers to sites where tigers had killed their cows, buffalo, goats or pigs. Villagers in Kanha (and many protected areas worldwide) report these locations to receive financial compensation and subsidise the income losses of coexisting with big cats. But kill sites offer far more than just blood, bones and a queasy stomach; they offer a wealth of insight into how tigers hunt.

In combining site GPS coordinates with landscape features like villages, roads and vegetation cover, we found that tigers targeted livestock at sites with certain characteristics but not others: close to forests. Far from villages, roads and agricultural fields. All not especially surprising, considering that tigers are notorious for hunting in dense forest away from human activity.

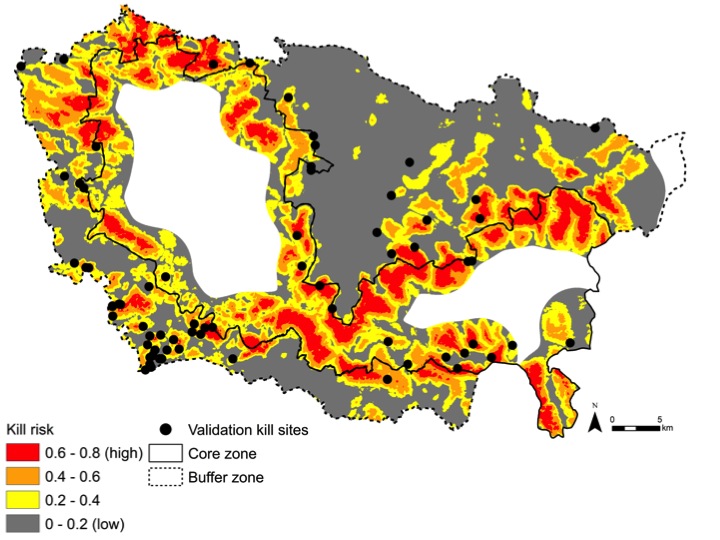

However, when we mapped the statistical models, results become far more informative as a tool for conservation. Hotspot maps visually showed the relative risk of a tiger attack, from gray (low risk) to red (high risk). These maps brought risks closer to home: I could compare the odds of a tiger killing a cow in my own backyard to my neighbour’s backyard.

In the hands of a livestock owner or a park manager, such a map could be quite useful for spatially strategising to deter carnivore attacks: Graze livestock in lower-risk, accessible areas. Strengthen enclosures in high-risk areas. Build fences to keep livestock out of high-risk forests. Boost financial compensation for villages in high-risk regions. The strategies are limitless.

Of course, such methods spark as many questions as they answer. If models depend on densities of livestock and carnivores, as they should for enhanced accuracy, shifting grazing into low-risk areas could change risk distributions. Likewise, seasonal changes in resources, such as water, might affect landscapes of risk. Yet with GPS data from the latest livestock kill sites, the models and maps can be updated to reflect the latest (or long-term) hotspots, offering an adaptable tool.

This risk map shows the relative probability of a tiger killing livestock in Kanha. Risk hotspots (red) were located in the dense forests along the boundary between the protected core zone and human-dominated buffer zone boundaries.

Risk models and hotspot maps aren’t particularly new. Over the last decade they’ve been developed for wolves in the U.S., jaguars and pumas in Mexico and even tigers in India (with varying techniques). But they have yet to be embraced by the conservation community and fully explored as a practical tool for aiding stakeholder, management and policy decision-making. My hope is that a bit of new science will help us better utilise such simple yet powerful tools for guiding our efforts to beat the odds and save the tiger.

This paper is freely accessible at Ecology and Evolution.

Citation: Miller, J. R. M., Y. V. Jhala, J. Jena and O. Schmitz. 2015. Landscape-scale accessibility of livestock to tigers: implications of spatial grain for modeling predation risk to mitigate human–carnivore conflict. Ecology and Evolution 5(6):1354-1367.

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.