- Full paper published in Nature PDF File

This year, India surpassed China to become the world’s most populated country with over 1.4 billion people. As we move towards a time of climate uncertainty, the country continues to straddle between high dependency on natural resources on one side, and aspirations of becoming a global economic superpower on the other. In such a scenario, how can we reimagine conservation in a manner that is just and equitable to all Indians? In 2020, the Government of India’s National Mission for Biodiversity and Human Well-being (NMBHWB) set up a working group to mainstream biodiversity conservation with the country’s discourse on economic development and human well-being. The working group engaged with 18 field and domain experts from 15 Indian and international institutions to implement a landscape-scale prioritization exercise.

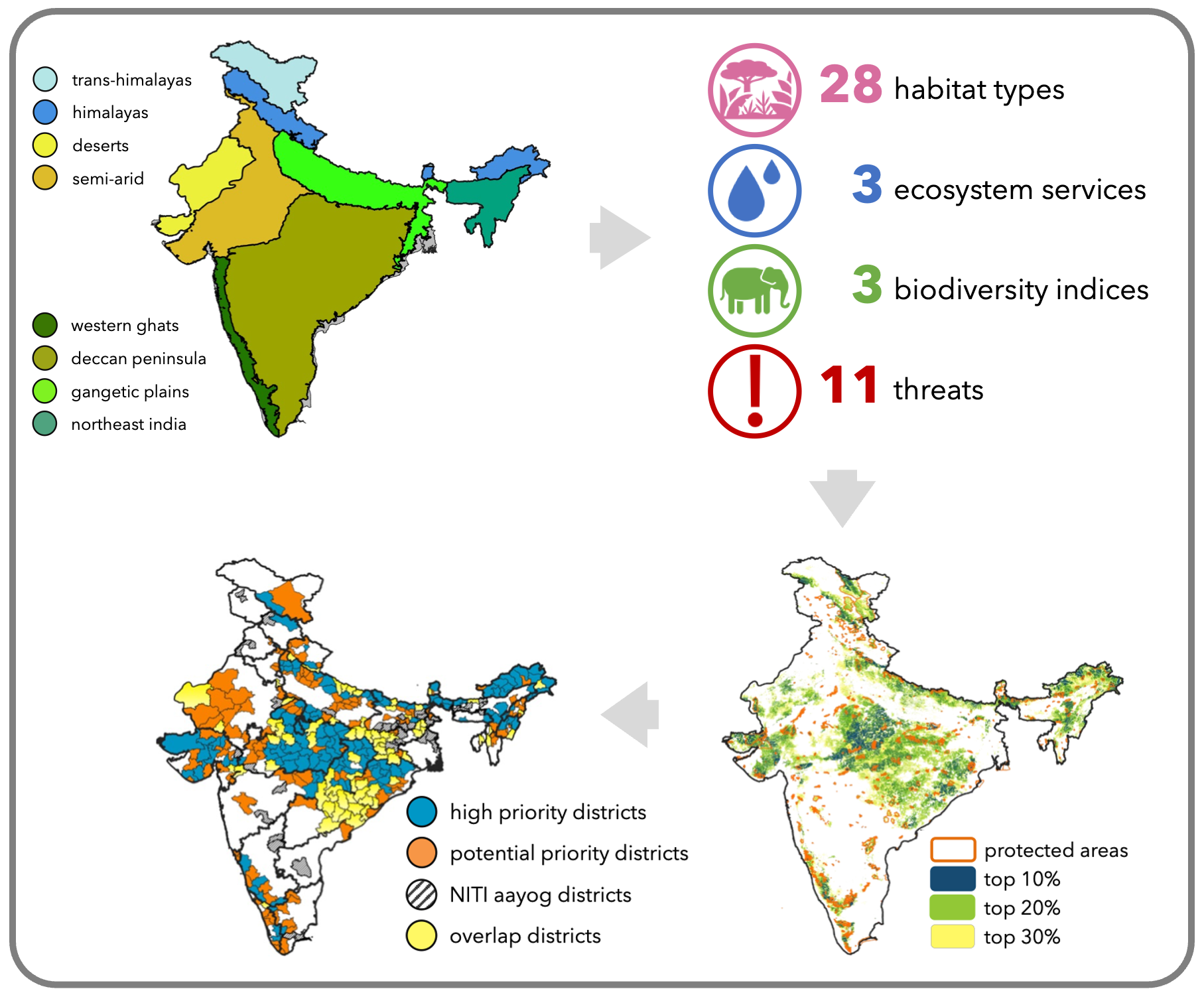

We set out by first selecting 8 of India’s 10 biogeographic zones–– (i) trans-Himalayas, (ii) Himalayas, (iii) deserts, (iv) semi-arid, (v) Western Ghats, (vi) Deccan plateau, (vii) Gangetic plains, (viii) Northeast India. Within each of these zones, we chose 4 broad themes based on which to undertake priority-setting–– (i) Habitats, which included all dominant, natural or rare, vulnerable habitats, (ii) Ecosystem Services, like water supply and carbon sequestration, which are closely linked to human well-being, (iii) Biodiversity, the diversity of threatened species, biodiversity hotspots, and locations with putative source populations, and (iv) Threats, to encapsulate human pressures on ecosystems. We used Spatial Conservation Prioritization to generate maps of priority landscapes in each zone. We then demarcated the top 30% priority areas in India (~850,000 sq.km), to align with the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework and COP15 targets.

This zone-wise, theme-wise approach to prioritization is unique in that it tapped into the diverse knowledge and experience of the working group members. For instance, our priority areas included many rare and vulnerable habitats (savanna grasslands, ravines, hot and cold deserts, rocky boulders, and escarpments) that are routinely ignored in conservation discourse. In terms of the Threats, we observed compounding effects of crop-land expansion and urbanization, combined with increased linear infrastructure (roads/railways) and increased year-round irrigation in agricultural areas. A key point here is that only 5% of India’s land area is under the current Protected Area (PA) network, and these PAs constitute only 15% of the 850,000 sq. km priority regions in the country. Our appeal is therefore to adopt a landscape-scale approach to safeguard priority areas and view them as shared ‘conservation landscapes’.

To realize our proposed actions, effective and equitable models of governance that capture and represent the complexity and diversity of socio-ecological systems must be urgently adopted in environmental and conservation policy. To make our results policy-relevant, we overlaid India’s district boundaries on the priority map, with an emphasis on Govt. of India NITI Aayog’s economic aspirational districts. We identify 338 units as either ‘high priority’ districts (169) or ‘potential priority’ districts (169). In high priority districts, the need is to deprioritize mega-infrastructure projects, maintain existing habitats, ecosystem services, and biodiversity via state-driven and participatory approaches. In the potential priority districts, in addition to preserving existing habitats, the key focus must be on implementing species rewilding, agroforestry, ecological restoration, and other nature recovery strategies integrated with district- and state-level plans.

Ours is perhaps the first comprehensive countrywide assessment that attempts to redefine frameworks for landscape-level prioritization at policy relevant eco-socio-administrative dimensions. Yet, this is only a start-point. We provide a pathway to achieve India’s Sustainable Development Goals in complex human–natural conservation landscapes; a pathway that acknowledges the combined needs for biodiversity conservation and economic development, one that enables ecosystem services to benefit the poor while simultaneously acknowledging the limitations and trade-offs in doing so.

Citation: Srivathsa, A., Vasudev, D., Nair, T., Chakrabarti, S., Chanchani, P., DeFries, R., Deomurari, A., Dutta, S., Ghose, D., Goswami, V.R., Nayak, R., Neelakantan, A., Thatte, P., Vaidyanathan, S., Verma, M., Krishnaswamy, J., Sankaran, M., Ramakrishnan, U. (2023) Prioritizing India’s landscapes for biodiversity, ecosystem services and human well-being. Nature Sustainability. doi: 10.1038/s41893-023-01063-2

Weblink: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-023-01063-2

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.