Of the 69 species of raptors known from India, Amur Falcon (Falco amurensis) was one of the least talked about species till recently. Primarily recorded from northeast India, with a few scattered sight records in peninsular India, the species is generally considered rare. All that changed following a report by Conservation India in October 2012 of the massive large scale harvest of these falcons in Nagaland. Researchers estimated that between 120,000 and 140,000 individuals were being trapped and killed for human consumption in just one location in Nagaland at the Doyang roost site in Wokha district each year (Dalvi et. al. 2013).

Weighing 160–200 g, Amur Falcon is a small bird of prey and is a long distance, trans-equatorial migrant (Bildstein 2006), travelling from eastern Asia all the way to southern Africa and back every year. Annually, in early autumn, these migrant falcons leave their Asian breeding range and travel to parts of northeast India and Bangladesh that act as staging areas for the overland flights across India (Ali & Ripley 1987; Naoroji 2007). In northeast India, they are known to collect in flocks numbering thousands, to feed and rest before continuing their journey. Subsequently, they undertake the longest regular overwater migration of any bird of prey, crossing over the Indian Ocean between western India and tropical east Africa, a journey of more than 4,000 km, which includes nocturnal flight (Bildstein & Zalles 2005). This species is adapted to the strong monsoon tailwinds, which results in its late arrival in eastern Africa in autumn (Ash & Atkins 2009). Migrants are said to arrive in their southern African winter range in November-December and depart by early May (Mendelsohn 1997). The spring passage route is not clearly known, and it is suspected that they fly across the Arabian Peninsula, north through Afghanistan and then to East Asia (Ali & Ripley 1987; BirdLife International 2014).

Hard-hitting images of the large-scale harvest of Amur Falcons in Nagaland led to an international outcry from conservation organisations and individuals across the world. The Government of India, at both state and national levels, acted promptly, bringing an immediate ban on hunting. The Nagaland State Forest Department, along with several non-governmental organisations, initiated extensive conservation education programmes. The latter resulted in the local people coming forward to protect the Amurs when they arrived in October 2013.

This incident brought to notice not only the extensive hunting of the species, it also generated an awareness that large numbers of Amur Flacons pass through Nagaland. This migratory stop-over and roost is believed to be by far the largest and most spectacular roost of any species of falcon ever seen. Currently, there are no clear estimates of the population passing through the region, and the migratory routes and other stop-over sites across India are unknown. India, being a signatory to the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS), is duty bound to prevent hunting, and provide safe passage, as well as draw up appropriate action plans for the long-term conservation of this bird.

One such plan was to satellite track Amur Falcon to better understand their behaviour and ecology during their presence in Nagaland, along the migration routes, and in the wintering areas in Africa. Using web-based tools, the information gained was also to be actively applied to raise awareness of the international importance of this species and to promote falcon conservation, particularly among local communities in Nagaland.

A joint mission to satellite tag Amur Falcons in Nagaland between November 4–9, 2013 was thus initiated by the Wildlife Institute of India in collaboration with Nick Williams, Head of the Coordinating Unit of the Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Birds of Prey in Africa and Eurasia (Raptors MOU); Hungarian ornithologists Peter Fehervari, Szabolcs Solt, and Peter Palatitz; and the Nagaland State Forest Department. The Hungarian ornithologists had several years experience studying the closely related Red-footed Falcon Falco vespertinus, which also included a study to track their migration from Europe to South Africa.

At the Doyang roost site, after several attempts over three days, 30 Amurs were finally trapped using mist nets on the night of November 6, 2013. Three of them in good feather condition, and appearing to be in good health were selected for the satellite tagging. One male was named Naga in short for Nagaland; one female was named Wokha after the name of the district which is globally important for its roost site; and a second female was named Pangti after the village located in Wokha district and in recognition of the efforts made by the people of Pangti to protect these falcons. The birds were fitted with the state-of-the-art 5 gram Solar-Powered PTT (Microwave Telemetry Inc.), like a backpack using a specially made teflon harness, and released in the morning of November 7. All the birds were ringed with a BNHS metal ring on the left leg and a colour-coded plastic ring on the right.

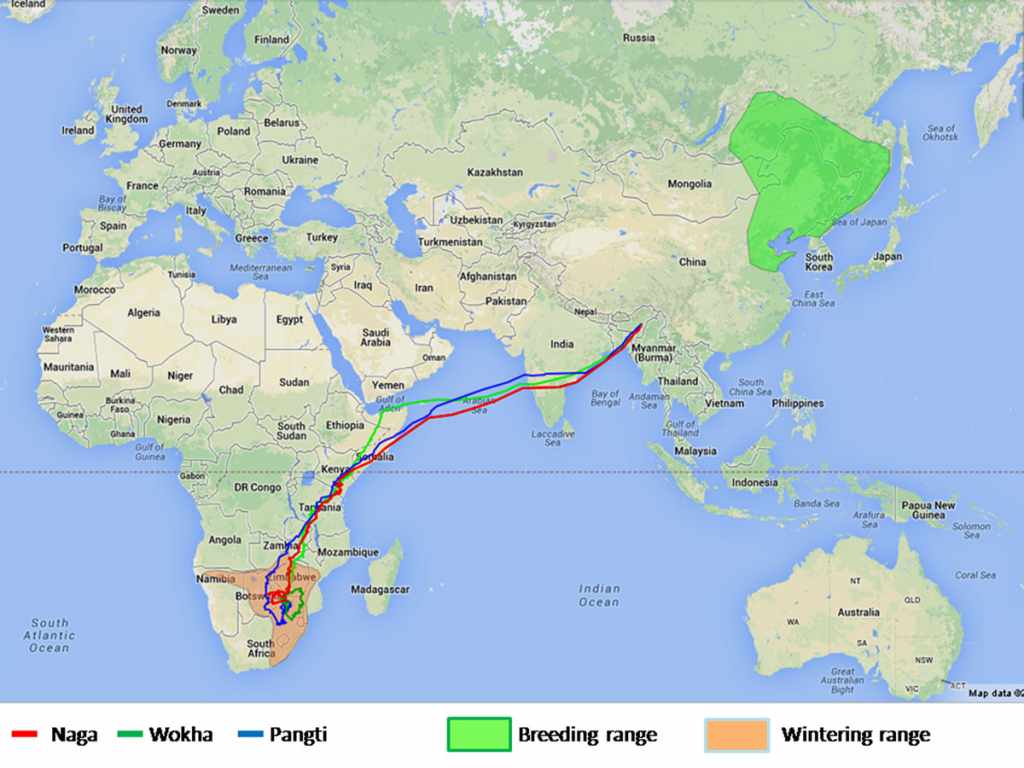

On the morning of November 10 (08:00 hrs), Pangti was the first to depart on the south bound migration from her roost along the Assam-Manipur-Nagaland border. Naga was the next to leave on November 11 (11:00 hrs), and then Wokha departed on November 13 (05:30 hrs). Both Naga and Wokha roosted for a night in the hills along the Mizoram-Tripura border. All three birds flew non-stop first southwest over Bangladesh and then over the Bay of Bengal for a day to arrive at the Andhra Pradesh coast, covering an over-water distance that ranged from 600 to 1,300 km. Pangti and Wokha flew into Andhra Pradesh north of Visakhapatnam, while Naga made the crossing at the Krishna river delta south of Machilipatnam. The falcons then travelled west to arrive on the western seaboard of India on the second day. En route, Pangti stopped for a night just south of Satara in Maharashtra, while Wokha stopped at a site along the Andhra Pradesh-Karnataka border north of Raichur town. Incredibly, Naga continued to fly nonstop and entered air space over the Arabian Sea around 20 km south of Panaji, Goa and flew across to arrive at the northern African shore of Somalia on the morning of November 16. Naga made an incredible nonstop flight from NE India, covering a distance of 5,600 km in 5 days and 10 hrs, flying at a speed of 40 km/hr. Pangti entered over the Arabian Sea about 150 km south of Mumbai and also arrived at the Somalian Coast, south of the Horn of Africa on the evening of November16. Wokha, who departed late, took a longer oceanic route and arrived at the Somalian Coast in the Gulf of Aden. The Arabian Sea crossing was c. 2,800-3,000-3,060 km and lasted 82-77-72 hours for Pangti-Naga-Wokha respectively. All three birds were assisted by tail winds of the north-easterly trade winds of about 20 km/hr.

Satellite tracking Amur Falcons — the routes of the three falcons in season one

The behaviour of the falcons changed after arriving in Africa with frequent stops and by December 25, all three birds arrived in their wintering range in southern Africa.The migratory routes of the falcons converged at several locations along the route passing through Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana, and South Africa. One of the major stop-over sites of the three falcons en route to South Africa was the Tsavo East and West National Park in southern Kenya. Naga spent nearly one month moving within a radius of c. 7,000 sq. km in the Tsavo East National Park before heading south. Pangti was the first to arrive in South Africa, and she first moved around the Transvaal region before settling down at a site west of Johannesburg, where she spent 75 days. Wokha was the next to arrive in South Africa and made similar movements before settling down at a site far south close to the South Africa-Lesotho border. There, Wokha stayed for 68 days before the transmission was discontinued, as she appeared to have died or the transmitter was thought to have fallen off. Naga only arrived as far south as Botswana where he remained at a site bordering the Central Kalahari Game Reserve for 68 days.

Naga started his return migration on March 21 from Botswana, while Pangti started on April 3 from South Africa and within a span of 16 and 20 days both the birds arrived in Somalia. They returned to the same spot where they had arrived on their south-bound autumn passage. After spending a few days in Somalia, Naga departed on the open sea, crossing on the afternoon of April 18. This time again Naga made nonstop flight across the Arabian Sea, then across India, and stopped for a night in northern Myanmar. The return migration route of Naga was further north and along the Arabian Peninsula, and made landfall at the Gujarat coast, north of the Gulf of Kutch. Pangti followed the same route as Naga, even though the latter had departed 22 days ago. Both the falcons did not return to the Doyang roost site in Nagaland and instead flew across south through Manipur state and into Myanmar.

The two falcons then flew east and southeast along the Myanmar-China border. After a few stops in southern China and along the China-Vietnam border, Naga changed direction to fly north and arrived on May 7 at its likely breeding site located 500 km northwest of Beijing. Pangti flew across into Laos and after a few stops in Vietnam also turned north to arrive at a site 350 km west of Beijing. While the two falcons have currently arrived in their breeding range, which is c. 9,000 km from the shores of Somalia, it is yet to be known whether they will fly further north. The migration routes of the falcons tracked across India coincides with the innumerable sight records of the species along the west coast of India. Interestingly, though there are a number of sight records of Amur from Sri Lanka and Maldives, most falcons fly non-stop to Africa on the sea. Furthermore, there are a number of sight records from Nepal and northern India. Are these birds part of the population that arrives in Nagaland or are they a different population that migrates across the Himalaya, and is still to be known? It is hoped that the two falcons, Naga and Pangti, will return to Nagaland in October this year and provide more insights on their incredible ability to travel half way across the globe each year.

References:

- Ali, S. and Ripley, S.D. (1987) Compact Edition of the Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan. Oxford University Press, New Delhi.

- Ash, J. and Atkins, J. (2009) Birds of Ethiopia and Eritrea: An Atlas of Distribution. Christopher Helm, London.

- Bildstein, K.L. (2006) Migrating raptors of the world: their ecology & conservation. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York. 336 pp.

- Bildstein, K.L. and Zalles, J.I. (2005) Old World versus New World long-distance migration in accipiters, buteos, and falcons: the interplay of migration ability and global biogeography. In: Greenberg, R. and Marra, P.P. (eds.). Birds of two worlds: the ecology and evolution of migration. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. Pp.154–167.

- BirdLife International (2014) Species factsheet: Falco amurensis. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 23/06/2014.

- Dalvi, S., Sreenivasan, R. and Price, T. (2013) Exploitation in Northeast India. Science 339 (6117): 270–270.

- Mendelsohn, J.M. (1997) Eastern Redfooted Kestrel Falco amurensis. The Atlas of South African Birds 1: 262–263.

- Naoroji, R. (2007) Birds of Prey of the Indian Subcontinent. Om Books International, New Delhi.

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.