Cruising through a canal after dusk in the heart of the tiger-swamp certainly sounds most daunting. The glimmering eyes of fish owls perched on overhanging trees, alarm calls of spotted deer, and the soothing sounds of the rowing boat make for a enthralling journey, whose climax reaches its highest peak if a tiger roars close by! Those who have spent a little time in the mangroves of the Sundarbans would clearly understand what I am trying to portray, and the uniqueness of it.

Well, other than tigers, crocodiles and deer, the Sundarbans is home to many fascinating life forms that we hardly hear about. There are many captivating species in this unique mangrove forest, little known to science, but which hold the dubious distinction of being in the world’s threatened species lists.

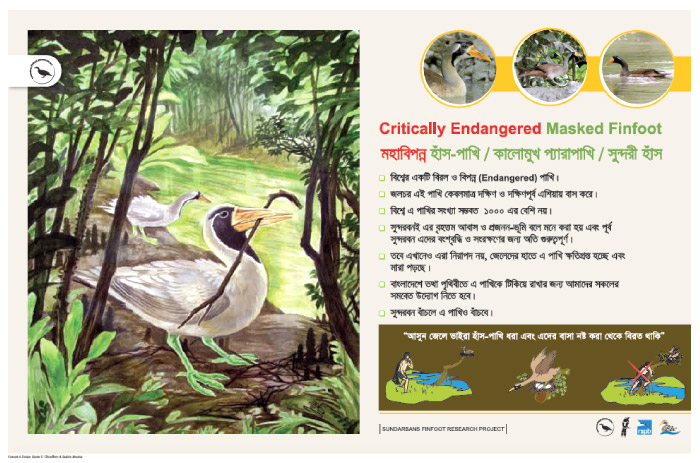

One of these ‘only-found-in-the-Sundarbans’ species is the enigmatic Masked Finfoot (Heliopais personata). A peculiar duck-like bird, it has been placed in its own family by taxonomists, along with only two other similar birds, found in Africa and South America respectively. Finfoots are named for the lobes on their feet, which enable them to swim well, as well as to clamber about among fallen trunks and branches of dense mangrove forest.

While only a thousand or less mature individuals of Masked Finfoots are left in the world, the Sundarbans support a considerable number. BirdLife International classifies the species as Endangered, due to the destruction and increasing disturbance to rivers in lowland riverine forests, hunting, and the collection of eggs and chicks for food. Masked Finfoots are thinly distributed from India (old records from northeast), Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam to peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, Java, and Indonesia, but the Sundarbans of Bangladesh remain a definite place to see this elusive bird.

Very little is known about its breeding biology, population trend and potential threats in important sites. The ‘Sundarbans Finfoot Research Project’ is now working to better understand the breeding biology of the Masked Finfoot. Efforts are on to estimate its population in the Sundarbans, and to identify conservation threats and hotspots, in order to inform the government and other stakeholders about the conservation measures for the species.

As we struggle to save endangered mega-fauna like the tiger or elephant, it is even more challenging to think about overlooked species like the Masked Finfoot – so rare and elusive that till date very little is known about its biology and ecology. To understand more about this highly threatened species, we braved the hot, humid, and wet summer to find Masked Finfoots and their nests in the Sundarbans of Bangladesh.

Even the ones with not-so-adventurous-hearts get excited at the thought of visiting the Sundarbans and exploring her mysteries, and our team held people who were seeking not just adventure but knowledge about the most mysterious bird in the largest mangrove forest in the world. Since 2011 we have spent 130 summer days on a boat, seeking the secrets of the finfoots. The days were long, for we were at the mercy of the tide, starting at dawn and sometimes ending after dusk. From our boat we got on a small dinghi and searched never ending khals (narrow creeks) along the eastern side of the Sundarbans of Bangladesh. Starting from Chadpai up to the Sarankhola range, covering more than 100 sq km, we found 25 nests, of which five were active. Our dinghi traversed up and down the canals, at times with nothing but hope in our hearts. Through the heat of July, the monsoon rains of August, the starting of Ramadan and breaking of the fast our search for the bird continued.

There were days when we came back with fuller spirits, having spotted Masked Finfoots foraging during low tide, and there were days when nothing, absolutely nothing was found, except for watching the common and blue-eared kingfishers, hearing the calls of the Mangrove Pitta, and spotting footprints of the spotted deer. We were delighted at finding an active nest, having overcome all manner of uncertainties: dealing with the changes in the tides, the mysterious jungle, the venous canals, and our fading confidence.

To observe and document the Masked Finfoot’s nocturnal behaviour for the first time, we set up camera traps in a safe location so as to not disturb the Masked Finfoot couple, and also watched them from a hide. We took turns and kept a watch to learn more about their behaviour, feeding habits, and patterns of incubation. Most of these data were new to science and we were extremely excited to share this with others.

Looking back at the last couple of summers, and our quest in the Sundarbans to understand and help the survival of Masked Finfoots, there are many memories that come to mind. Strangely it’s not the hardships that I see, but the positives: the finding of the nest, the attachment to the Masked Finfoot families, comprehending their behaviour, and later taking steps to improve their condition.

We interviewed fishermen on the way; more than a hundred so far, and almost all of them had hunted or at least tasted Masked Finfoots once in their lifetime! Most of them had captured Finfoots, or found their nests while setting up Charpata Jaal (fishing nets) along narrow streams in the Sundarbans. Charpata fishermen usually set up long fishing nets at low tide along banks of khals, and harvest fish after high tide. Many of them flushed incubating finfoots while affixing Charpata nets either underneath or near nests, and came back at night to grab the unfortunate finfoot, its eggs or chicks from the nest. We are now working with the Forest Department of Bangladesh in order to find a long-term solution to the opportunistic hunting of finfoots. We want to change the habits of the fishermen, for Charpata net fishing to be done on a limited basis in Masked Finfoot zones, especially during the breeding season; we want to go to villages of the fishermen and make them understand what they do not know yet, about the gems they have and are destroying due to being unaware. Most importantly, we want to continue our work, with more research and more findings to help the Masked Finfoots increase in numbers.

Finfoot Facts and New Findings

| Global population estimate by BirdLife International | 600-1700 mature individuals, possibly much less |

| Population in the Sundarbans, Bangladesh | Possibly largest in the world, 25 nests were found in the Sundarbans by SFRP so far. Analysis underway |

| Preferred nesting and foraging habitat | 5-25 meter wide and undisturbed creeks |

| Preferred nesting tree/s in the Sundarbans, Bangladesh | Sundri (Heritiera fomes) & Gewa (Excoecaria agallocha) |

| Incubation | On average the female (19.39±2.53 hrs/day) participated more in incubation than the male (3.30±3.37hrs/day) |

| Threat: hunting | A total of 16 adults were hunted, 15 chicks and 4 eggs were collected from the nests by local fishermen between 2007 and 2011. |

| Diet | Crabs (80.95%) and small shrimps (19.04%); (N=21) |

| Breeding hotspots in the Sundarbans, Bangladesh | Eastern Sundarbans: from Supoti to Chita-katka |

Masked Finfoot Facts

What is the Masked Finfoot?

Masked finfoot (Heliopais personatus) is an elusive and shy aquatic water bird that occurs mainly in the brackish waters of the eastern Indian subcontinent, Indochina, Malaysia and Indonesia. Sporting a prominent yellow bill and black face mask, this is one of the most beautiful species of waterbirds. Born with adaptive lobed green feet, the Masked Finfoot is a mangrove specialist. It is a master of waterways and the narrow banks where it forages for crabs, shrimps and fishes. Unfortunately only 1000 or less individuals survive in the wild today, and the species is considered endangered and declining.

What are the threats they face?

Due to fast-changing riverine landscapes and opportunistic hunting by humans, these elusive birds find themselves staring at extinction. Only the efforts of a few to save the last of our waterways and save this species from impending doom currently holds out some hope . The most imminent threat is opportunistic hunting by fishermen who come across the nesting sites while engaged in fishing; this is especially true of a method of fishing called Charpata, causing the population numbers to dwindle in the Sundarbans.

What can we do to help the Masked Finfoot in Bangladesh?

Like tigers in the Sundarbans, we want to raise the profile of the finfoots to help protect these magnificent symbols of our waterways. We want to continue our research and conservation work with the government and local community. You can help us to sustain this little initiative for fascinating finnies by sponsoring our field trips or by joining us during the surveys between June and August every year.

Team Members of SFRP: Gertrud Denzau, Yann Muzika, Nazim Uddin Prince, Sakib Ahmed, Abida Rahman, Onu Tareq and Sayam U. Chowdhury.

View a short video of the Sundarbans Finfoot Research Project:

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.